2.5 Vector Subsetting and Modifying Values

So far, we’ve learned fundamental knowledge of 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3. In this section, we’ll start with how to create named vectors. Heads up, the process of creating a named vector is different from object assignment, and you’ll see the difference immediately.

2.5.1 Named Vectors

Remember in Section 1.3, we learned to give a name to an object by using the assignment operator <-. Depending on what name you assign to an object, it may provide a broad but unspecified explanation of the element(s) the object contains. When necessary, we need a way to label each element of an object to have a concrete idea on what each element refers to. To do so, We can turn an vector into an named vector, and there are two ways to complete this task.

a. Using the equal sign whilst creating the vector

If you have an object with a short length, you can consider using the form name = value inside the c() to create a named vector in one step.

In this example, we can see that the output includes a label for every arbitrary numeric value so that we know what these numbers mean in real life. For a named vector, you can also access its elements via the names, and update the values via the assignment operator.

x_w_name["height"]

#> height

#> 165

x_w_name["weight"] <- x_w_name["weight"] + 10

x_w_name

#> height weight BMI

#> 165 70 22b. Using the Names Function names() afterwards

While the equal sign method is straightforward, it is less effective when the object contains a few elements. In such cases, we can apply the Function names() after the vector is created. For example, if we want to represent whether it snows on each day using a logical vector during a ten-day time period.

y <- c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, TRUE)

y

#> [1] TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE

names(y) <- c("Jan 1", "Jan 2", "Jan 3", "Jan 4", "Jan 5", "Jan 6", "Jan 7", "Jan 8",

"Jan 9", "Jan 10")

y

#> Jan 1 Jan 2 Jan 3 Jan 4 Jan 5 Jan 6 Jan 7 Jan 8 Jan 9 Jan 10

#> TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUEAgain, the output after applying names() provides more information than before. You can also access element(s) and update their values via their names as we introduced just now. Reflectively, we can create an named vector whenever we want the vector itself to include more information, and the specific way to do that is really contingent upon our preferences and what we are given in each case.

Now, it’s important to be aware that the value for an element’s name need to be a character vector. Actually, an element’s name is also a type of attributes of R Objects. We will introduce other types of attributes as we encounter them. The name attribute provides additional information regarding the meaning of each element, and enables us to extract values using the names.

attributes(x_w_name)

#> $names

#> [1] "height" "weight" "BMI"

str(x_w_name)

#> Named num [1:3] 165 70 22

#> - attr(*, "names")= chr [1:3] "height" "weight" "BMI"

x_wo_name <- c(165, 60, 22)

str(x_wo_name)

#> num [1:3] 165 60 22You can see that x_w_name is a named numeric vector, with the names attribute. In contrast, str() function tells us x_wo_name is a plain numeric vector with no attributes. To directly extract certain attributes of an R object, you can use the attr() function on it with the second argument being the specific attribute you wish to extract.

2.5.2 Vector subsetting

Now, let’s delve into this section’s main focus: vector subsetting. At some point of your analysis of a vector with more than 1 element, you may want to extract particular elements to constitute a new vector. In R, the new vector is considered as a subvector of the original vector. This process is called vector subsetting, and the subvector will be of the same type as the original one.

In this part, we will introduce two common ways to do vector subsetting in R. Before we get started, let’s create a vector which will be used throughout this part.

a. Use logical vectors to do vector subsetting

Firstly, let’s see how we can apply logical vectors to do vector subsetting. Following the original vector’s name, a pair of square brackets [ ] is used to include a logical vector of the same length as the original vector. Here is an example,

From the result, you can see that the values from h with the same positions of TRUEs are extracted. Since 3, 4 and 90 are parts of the values of h, the vector composed of 3 4 90 is a subvector of h. When assigning these three values to a name, you will get a named subvector sub1. While sub1 is developed from h, they are now stored as two different vectors.

In addition to writing the logical vector in an explicit form, you can also use a named logical vector or an expression whose result is a logical vector. Let’s say we want to find the subvector of h for all elements in h that are larger than 2. Then, you can first compare h with 2, getting a logical vector, which is named big3 here.

Then you may notice that both big3 and h > 2 are identical to c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE). So, you can clearly put either big3 or h > 2 into [ ], which generates the same subvector with 3 4 90 as its elements.

Don’t restrict yourself in thinking that only numeric vectors can be subsetted. If you create a character vector home and compare it to "pig", you will get another logical vector same3. Let’s try to use same3 to do vector subsetting on h.

home <- c("pig", "monkey", "pig", "monkey", "pig")

same3 <- home == "pig"

sub2 <- h[same3]

sub2

#> [1] 3 4 90Awesome! You still get the result of 3 4 90! As a result, as long as the logical vector you apply in subsetting have the same logical values, you will get the same result after doing vector subsetting.

Of course, you can do vector subsetting on character vectors or logical vectors. Keep in mind that the result will be the same type as the original one. Try the following code by yourself.

home[same3]

#> [1] "pig" "pig" "pig"

home[big3]

#> [1] "pig" "pig" "pig"

lg <- c(TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, TRUE)

lg[same3]

#> [1] TRUE FALSE TRUE

lg[big3]

#> [1] TRUE FALSE TRUEb. Use indices to do vector subsetting

Next, we will introduce how to use indices to do vector subsetting. To achieve this goal, you need to put a numeric vector inside [ ], for example,

h #let's refresh ourself with what elements h contains

#> [1] 3 1 4 2 90

h[c(2, 4)] #return values of the 2nd and 4th elements of h

#> [1] 1 2As it shows, the values of the 2nd and 4th elements in h are returned. Notice that, in R, the first element in a vector has index 1, whereas other programming languages may have different indexing fashion. In that sense, the numeric vector inside the [ ] represents relative indices instead of actual numeric values. If you add a minus sign - before the numeric vector, you will get all elements except the 2nd and 4th ones in h.

Similar to using a named logical vectors, you can also use a named numeric vector to do vector subsetting.

The first line of this example looks like a new object assignment that assigns two numeric values, 2 and 4, to the name ind. However, what we really attempt is to restrict ind, a random name, to represent the 2nd and the 4th index.

Also, you can get subvectors of character vectors or logical vectors via indices.

In conclusion, there are two ways to get a subvector of h with values bigger than 2.

c. using names to do vector subsetting

For a named vector, we can also use character vectors consisting of the names as indices to do vector subsetting. The elements’ names and their corresponding indices are fungible.

2.5.3 Access and modify values in vectors and sub-vectors

We’ll end this section by learning the way to access and modify values in a vector. This is a fairly basic data manipulation, and the reason we wait until now to introduce it is because we use the same ways to access and modify values in atomic vectors that we presented in previous sections.

Let’s begin with extracting one element from a vector. To access a specific element, you can apply vector indexing by using the index of the element with a pair of square brackets [ ] surrounding it following by the vector name. After accessing an element, you can also update its value by using the assignment operator with the extraction expression on the left and the new value on the right. Let’s say you want to access the third element of y1 and update its value to 100.

It is as straightforward as it looks like! From the result, you can see that you’ve updated the third element’s value is updated to 100. Now, if you did look through the first half of this section, at this point you may find that accessing a vector’s element(s) is completed similarly compared to vector subsetting. It turns out we can update the values of multiple elements of a vector in a similarly way.

a. Change all values in subsets of vectors

Firstly, let’s review values of vector h and get a subset of it.

Obviously, you will get a numeric vector with 1 and 2 as the values. Let’s see how to change values for a subset of h. You just need to assign new values to the subset, then you can verify the values of h. Let’s see an example,

h[c(2, 4)] <- c(10, 20)

h

#> [1] 3 10 4 20 90

h[c(2, 4)] <- 10 #recycling rule applies

h

#> [1] 3 10 4 10 90In the first two lines, you can see that you have changed 1 and 2 to 10 and 20, respectively. In the last two lines, however, since you assign multiple values to one new value, R will apply recycling rule to complete the value updating process. In both cases, you have successfully change parts of h!

b. Define the vector again

Another way to change values in vectors is to do object assignment again using the same name, then you can change any values of it.

Let’s first reset the values of h.

From Section 1.3, you learned that you can check all objects you assigned and their values in the environment panel. So let’s review values of vector h from this panel together.

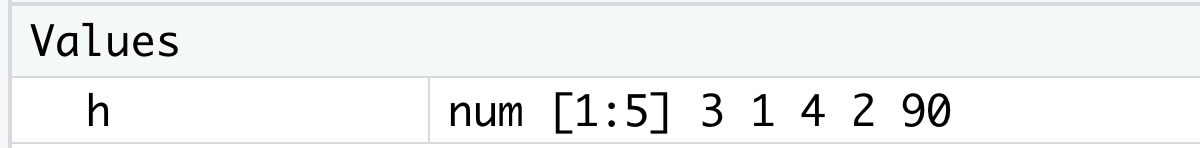

Figure 2.9: Values of h (1)

We should agree that h is a numeric vector with 5 values Then let’s try to do an object assignment again, this time you can assign different values to h and see what will happen to h.

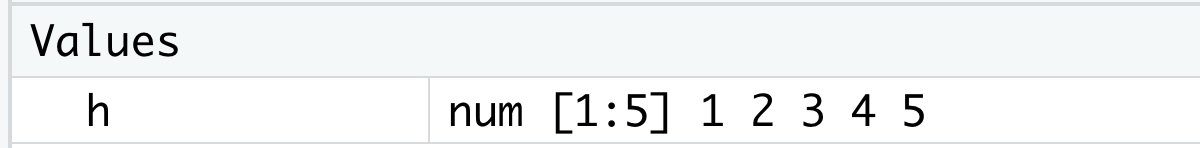

Figure 2.10: Values of h (2)

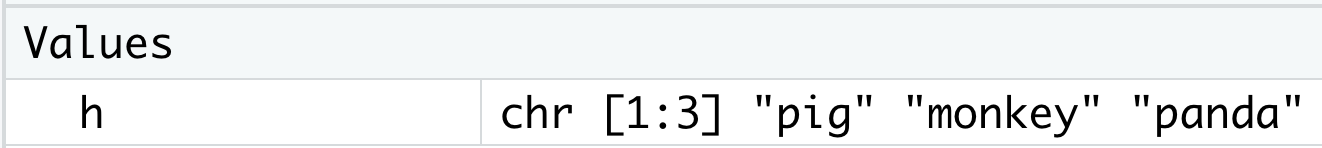

You can assign any values to h as you want, then h may change the vector type or even the object type according to the values assigned. By running the following code, h will be a character vector with three strings.

Figure 2.11: Values of h (3)

2.5.4 Exercises

Consider the vector v1 <- c(7, 2, 4, 9, 7), v2 <- c(6, 2, 8, 7, 9), and v3 <- 1:50.

Find the locations in

v1where the corresponding value is smaller thanv2.Find the subvector of

v2such that the corresponding location inv1is larger than 5.Find the subvector of

v3such that it is divisible by 7. (Hint: the result of7%%7is equal to 0 since 7 is divisible by 7)For all elements of

v3that is divisible by 8, replace it by 100.